In the complex political landscape of post-World War II Europe, few nations relied on sports as deeply for state-building and ideological projection as Socialist Yugoslavia under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito. For Tito and his government, sport was not merely a leisure activity or entertainment. It was a powerful political instrument—one capable of uniting a diverse federation of republics, promoting socialist ideals, and asserting Yugoslavia’s place on the global stage.

This article explores how sport was strategically used in Tito’s Yugoslavia to foster national cohesion, reinforce state ideology, and communicate the image of a progressive, modern nation to both domestic and international audiences.

Sport and the Yugoslav Identity

One of the greatest challenges faced by Tito’s government was holding together the multiethnic and multireligious structure of Yugoslavia. Comprising six republics and two autonomous provinces, the country included Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Bosniaks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Albanians, and others—many with their own historical grievances and aspirations.

Sport provided a rare and potent common ground. Unlike religion, language, or tradition, it offered a space where Yugoslavs of all backgrounds could rally behind a shared goal. National teams—whether in football, basketball, volleyball, or athletics—were carefully constructed to represent the country’s diversity. When the Yugoslav national football team took to the pitch, or the basketball team competed in international championships, they did so not as Serbs or Croats, but as Yugoslavs.

This constructed identity was reinforced in schools, youth organizations, and media, where young people were encouraged to participate in sports and identify with the successes of national teams. Winning games became winning for Yugoslavia—not just politically, but emotionally and culturally.

Tito’s Personal Role in Sports Promotion

Tito himself understood the symbolic power of sport. His leadership style combined authoritarianism with a strong emphasis on public appearances and mass participation events. He frequently attended major sporting events, hosted victorious athletes at state functions, and ensured that sporting achievements were featured prominently in the state-run press.

In 1948, just as Yugoslavia was expelled from the Cominform and isolated from the Soviet bloc, Tito doubled down on using domestic institutions—like sport—to cement internal cohesion. Athletic victories offered reassurance in times of diplomatic tension and helped foster pride in Yugoslavia’s unique “third way” of socialism, which was independent of both the USSR and Western capitalism.

Tito’s patronage of sport wasn’t only symbolic. State funding for athletic facilities, coaching programs, and mass sports events increased dramatically during his rule. Towns and villages across Yugoslavia built stadiums, gyms, and swimming pools. State-owned enterprises often sponsored local clubs, and the armed forces operated their own elite teams.

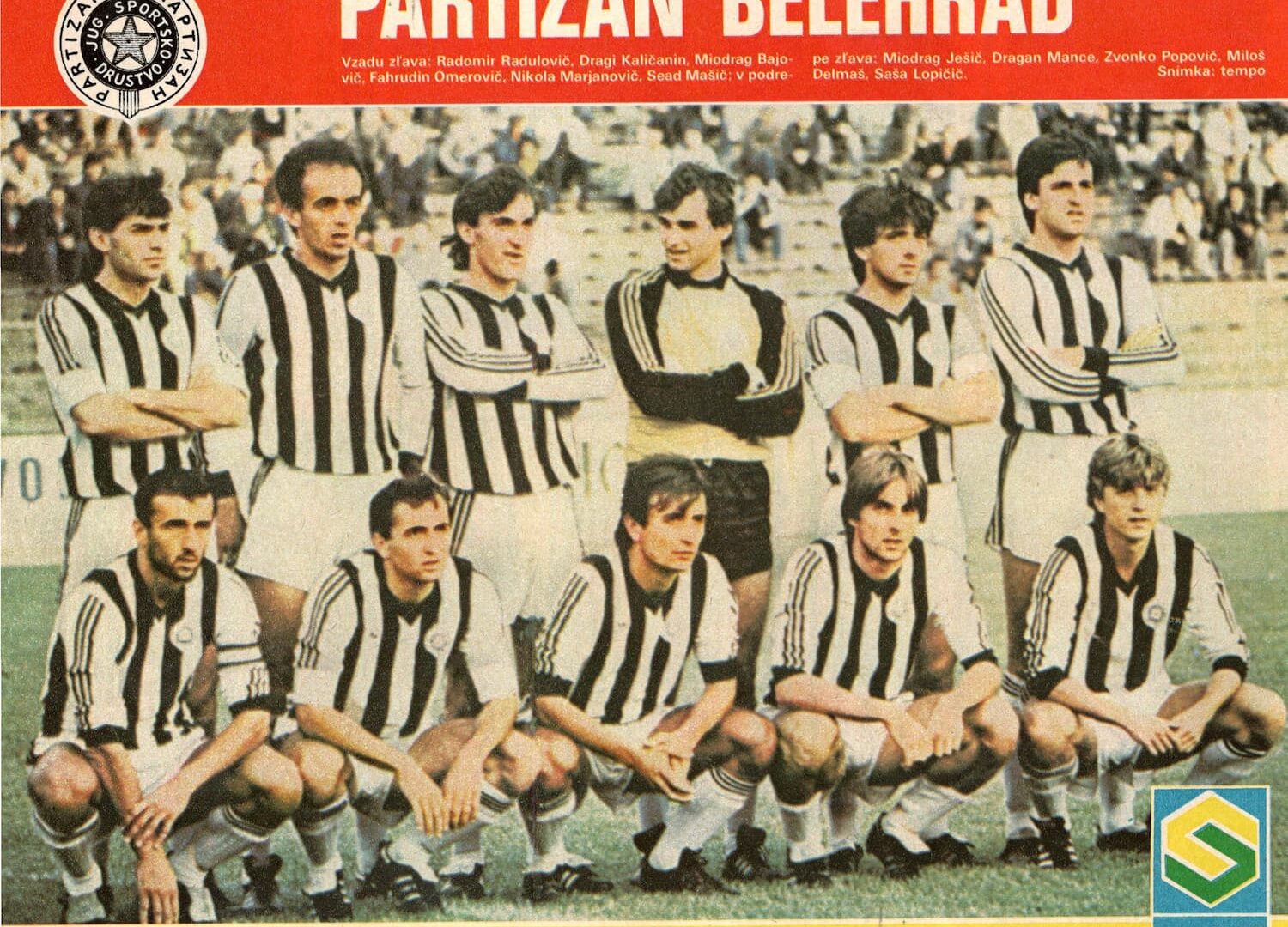

The Role of Partizan and Red Star Belgrade

Nowhere was the fusion of politics and sport more visible than in football, especially in Belgrade. The establishment of clubs like Partizan and Red Star Belgrade in the post-war period was not coincidental. Partizan was created by the Yugoslav People’s Army, while Red Star was founded by members of the Communist youth league. These clubs became not only powerhouses of football but also extensions of state institutions.

The fierce rivalry between these two clubs—known as the “Eternal Derby”—was closely followed across the country. While competition was intense, it was also channeled to reinforce unity, with both clubs representing the excellence of Yugoslav socialism on the European stage. When Red Star or Partizan played abroad, they did so as ambassadors of Tito’s Yugoslavia.

Mass Participation and the Partizan Sports Movement

Elite sport was only one side of the coin. Mass participation was equally emphasized, particularly through the “Partizan” sports movement, founded in 1945. With branches in schools, factories, and communities, the Partizan movement promoted physical education as a civic duty.

Tens of thousands of citizens were encouraged to take part in regular physical activities—not only for health, but as a demonstration of socialist discipline, cooperation, and productivity. Parades and synchronized gymnastic performances became common during state holidays, especially the “Day of Youth” celebrations, where thousands of young athletes would perform in stadiums before Tito.

These events, carefully choreographed and broadcast nationwide, reinforced the ideals of collective effort, physical vigor, and national unity.

International Sports as Political Messaging

Tito’s Yugoslavia also used international competitions to send strategic messages. Participation in events like the Olympics, the Mediterranean Games, and various world championships signaled that Yugoslavia was not an isolated or backward state, but a modern, active member of the international community.

The country’s athletes performed admirably, especially in basketball, handball, and football. Successes at global tournaments helped challenge stereotypes of Balkan instability and showed that a non-aligned socialist country could produce world-class talent. The medals and trophies brought home were not just personal victories—they were political capital.

In 1961, Belgrade hosted the first Games of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) countries, blending sport and diplomacy in a masterstroke of soft power. Sport helped define Yugoslavia’s position not as a Cold War pawn, but as a self-sufficient, independent actor.

Managing Ethnic Tensions Through Sport

Despite sport’s role in promoting unity, it also reflected—and sometimes inflamed—ethnic divisions. Local clubs were often seen as representing particular republics or ethnic groups. Matches between teams from Zagreb and Belgrade, for example, sometimes carried nationalistic overtones, especially in later decades as political tensions increased.

Tito’s regime managed this carefully. Violent incidents were met with swift crackdowns, and the media avoided framing events through ethnic lenses. However, as Yugoslavia moved into the 1980s and Tito’s death left a power vacuum, sport became a channel for growing nationalist sentiments. Chants, banners, and rivalries began to shift from playful competition to ethnic antagonism—foreshadowing the conflicts of the 1990s.

Conclusion: Legacy and Lessons

In Tito’s Yugoslavia, sport was never just about play. It was a deliberate, multifaceted instrument of statecraft. It was used to unite a fragmented society, to promote socialist ideology, and to elevate Yugoslavia’s image on the global stage. It succeeded in many ways: for decades, athletes were national heroes, sports facilities flourished, and international achievements were a source of pride.

Yet the story also serves as a cautionary tale. While sport can be a unifying force, its symbolism is powerful—and in times of political change, it can become a tool for division as easily as for cohesion.

Today, as former Yugoslav republics maintain strong sporting traditions, the legacy of Tito’s policies endures. Stadiums still bear witness to the grand visions of a state that once believed that through sport, it could build a better, stronger, more united society.